Scroll down for transcript

If you’ve been listening to this podcast over the years, you would probably know I’m a self-confessed Archibald tragic. I’m fascinated by the depiction of the human face and figure in paint and that is exactly what the prize celebrates each year at the Art Gallery of NSW.

The Archibald Prize is Australia’s most famous portrait prize and is now in its 100th year. This episode is a compilation of clips from my conversations with Archibald winners where they talk about how they felt about winning, what it did for their career or about the painting itself.

I’ve also included a clip from my conversation with biographer Scott Bevan where we talked about what was arguably the most controversial Archibald win – the 1943 winning portrait by William Dobell of fellow artist Joshua Smith.

To hear the podcast episode click ‘play’ beneath the above photo. Scroll down for the transcript.

See below for a list of podcast guests, the year they won the prize and their portraits. Click on the name to go to the full interview.

- Guy Warren 1985

- Davida Allen 1986

- William Robinson 1987 and 1995

- Francis Giacco 1994

- Wendy Sharpe 1996

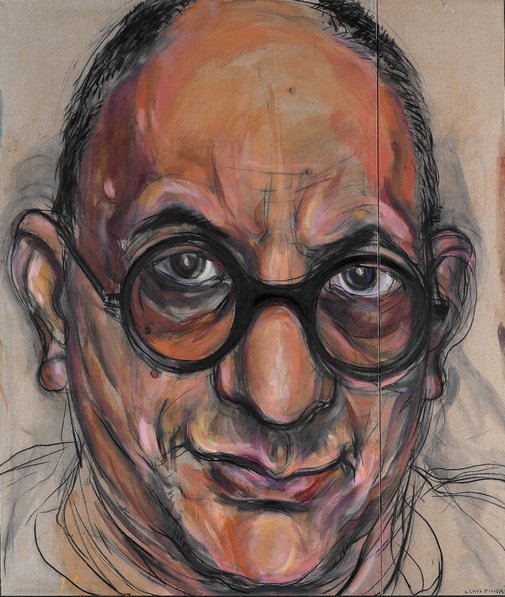

- Lewis Miller 1998

- Euan Macleod 1999

- Nicholas Harding 2001

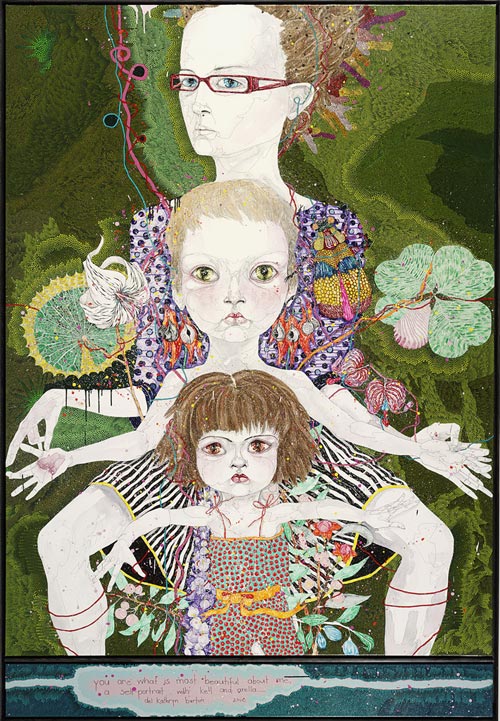

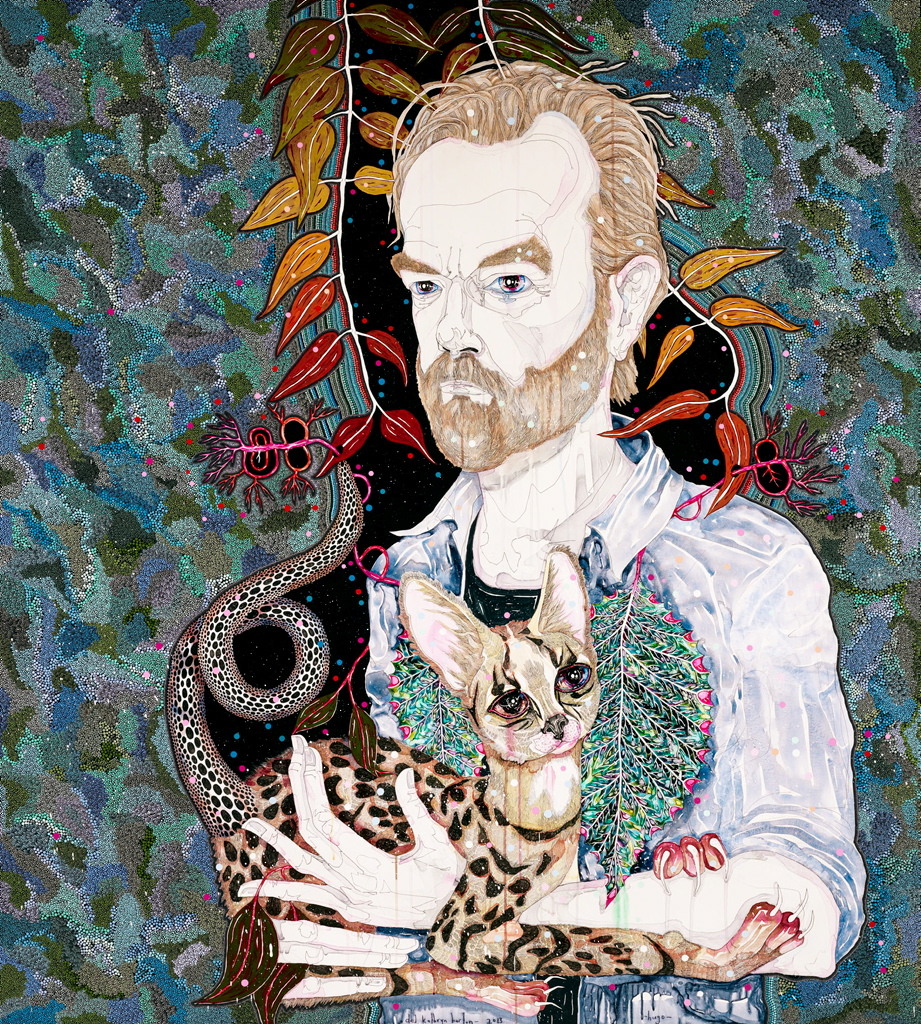

- Del Kathryn Barton 2008 and 2013

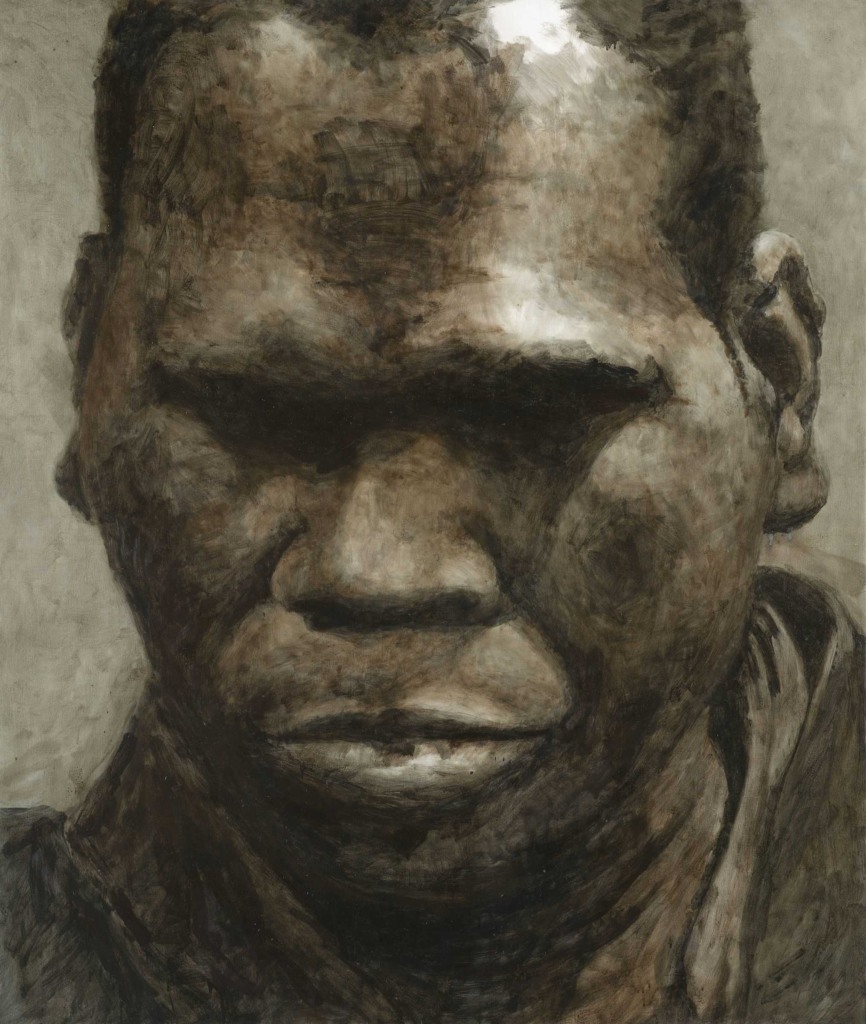

- Guido Maestri 2009

- Ben Quilty 2011

- Tim Storrier 2012

- Louise Hearman 2016

- Tony Costa 2019

- Vincent Namatjira 2020

- Peter Wegner 2021

- Scott Bevan

- ‘Archie 100’ exhibition – Art Gallery of NSW

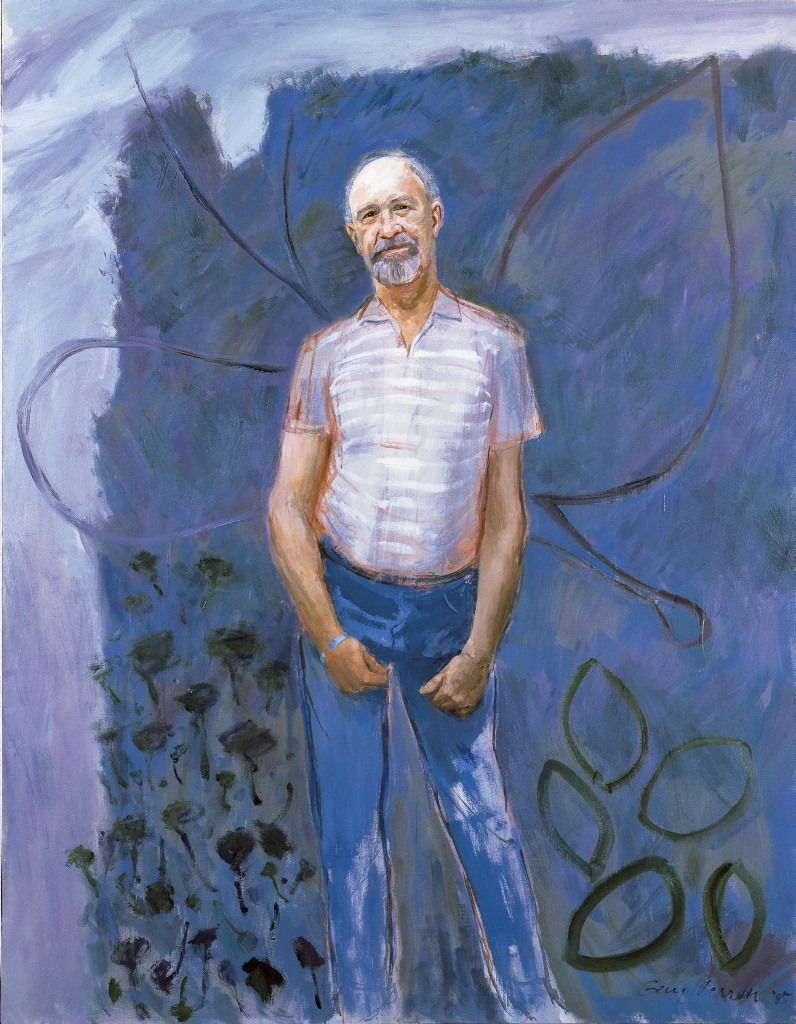

Winner of the Archibald Prize 1985

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

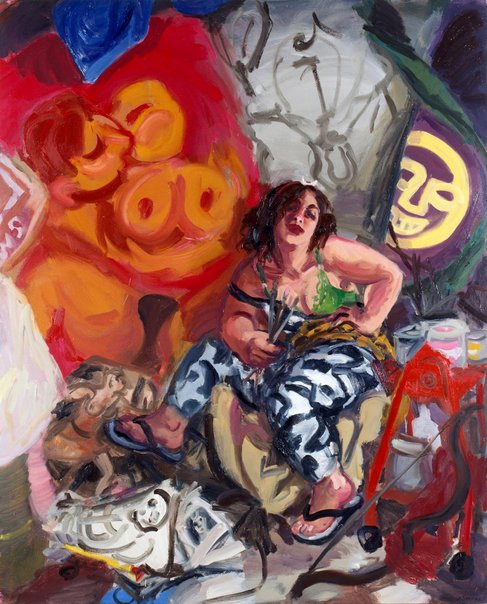

Winner, 1986 Archibald Prize, AGNSW

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

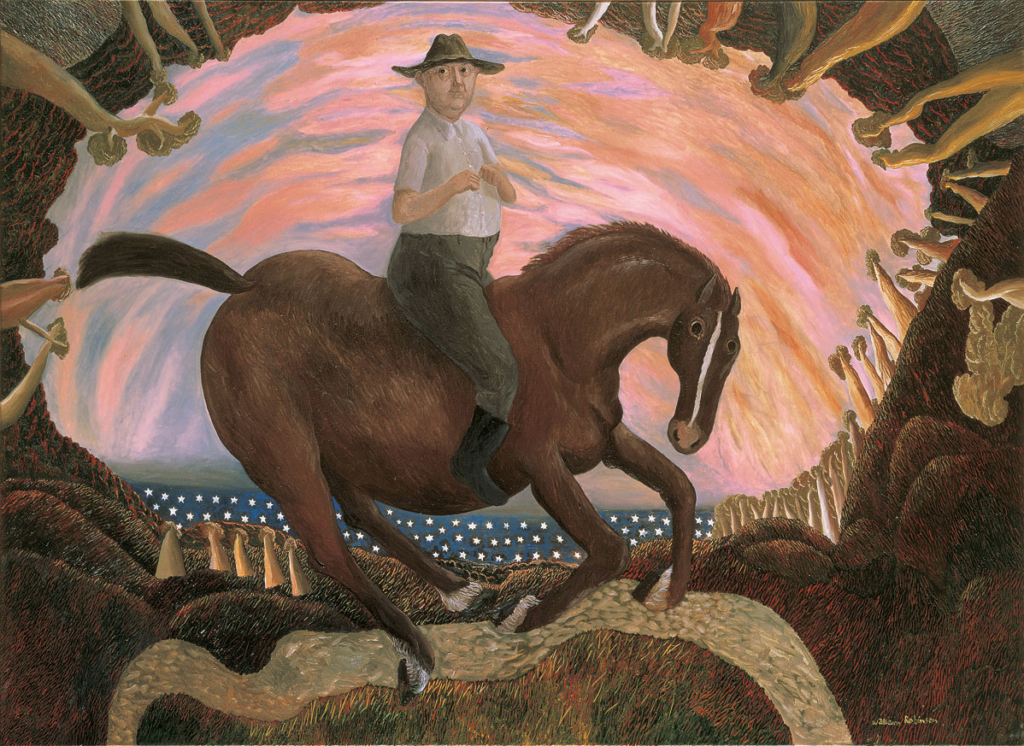

Winner Archibald Prize 1995

QUT Art Collection. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by William Robinson, 2011.

Winner Archibald Prize 1987

QUT Art Collection. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by William Robinson, 2011

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

‘John Bell as King Lear’, 2001, oil on canvas on board, 177 x 105cm (winner Archibald Prize 2001)

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

Winner Archibald Prize 2009, Art Gallery of NSW

Collection: National Portrait Gallery, Australia

Winner Archibald Prize 2011

Photo: AGNSW

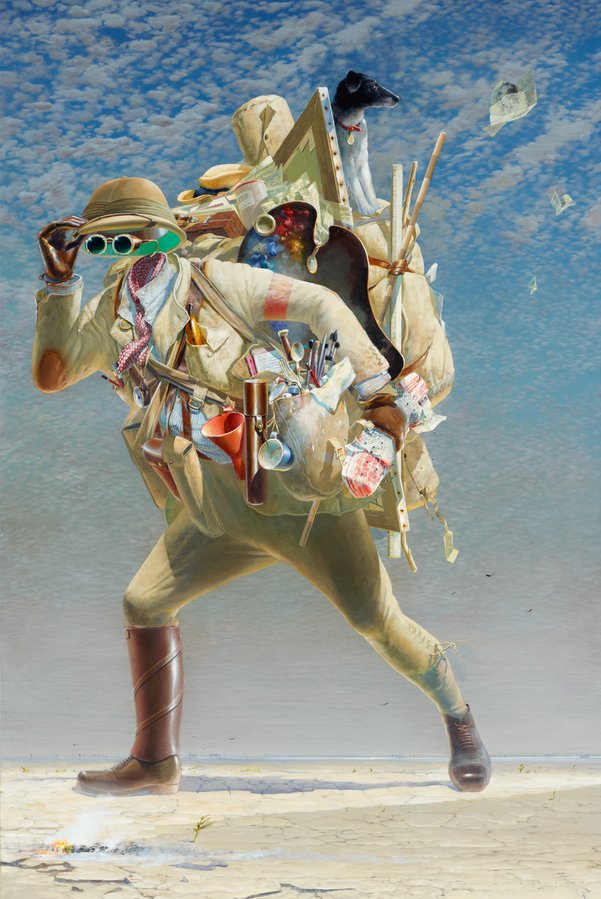

Winner Archibald Prize 2012

Photo: Art Gallery of NSW website

Photo: Art Gallery of NSW website

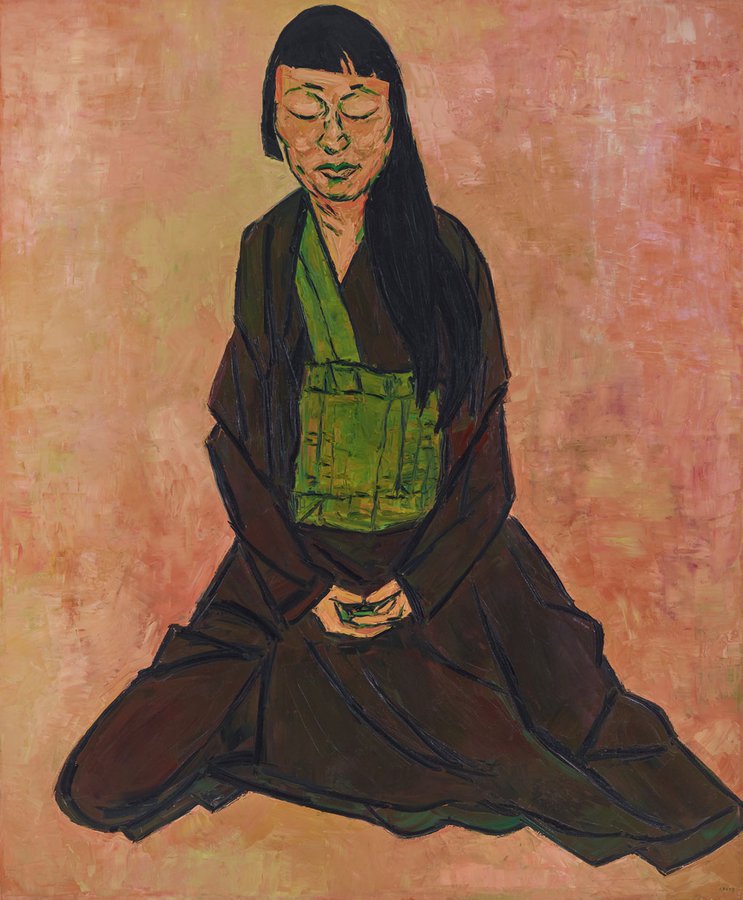

Winner Archibald Prize 2019, Art Gallery of NSW

Image: AGNSW website

Winner Archibald Prize 2020, Art Gallery of NSW

Image: AGNSW website

oil on canvas, 120.5 x 151.5cm

Image: Art Gallery of NSW website

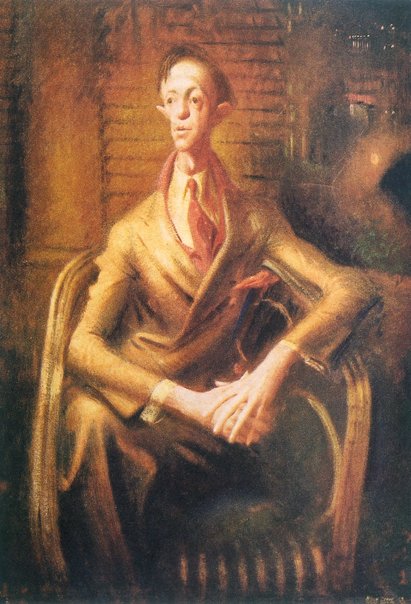

Winner of Archibald Prize 1943

TRANSCRIPT

Maria Stoljar 00:05

Hi, and welcome to Episode 115 of Talking with Painters where Australian painters talk about their lives and art. I’m Maria Stoljar, and I’ve got a special episode for you today, a compilation of clips of all the artists I’ve spoken to who’ve won the Archibald prize. What they’ve said about it, about the painting, about how they felt, about what it did for their career. For those outside of Australia who might not know what I’m talking about, the Archibald prize is Australia’s most famous portrait prize judged by the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. It’s currently worth $100,000, and this year, it turned 100. But not only that, it also brings with it a particular type of fame, which places that artist in Australian art history. So I’m going to chronologically go through all the Archibald winners that I’ve interviewed. There’s 15 altogether, including one upcoming guest, Peter Wegner, who I was supposed to interview a long time ago, but COVID came along and changed all that. So I’ve included some of his Archibald acceptance speech. The final clip is with biographer Scott Bevan, where we talk about arguably the most controversial Archibald when the portrait of Joshua Smith by William Dobell. All the works we talk about can be found on the website, talkingwithpainters.com, together with links to the full interviews with each of the artists. There will also be a video on my YouTube channel with an edited version of this episode in a few weeks, and I’ll be posting it to the show notes as well. So if you’re listening to this anytime after 2021, you’ll see it there. We start this episode in 1985, when Guy Warren won the prize with the portrait of his friend, artist, Bert Flugelman and back in the 80s, the prize didn’t have quite the same reputation as it does today. Talking about winning prizes, you were recognized in 1985, winning the Archibald prize with your wonderful portrait of Bert Flugelman who was a friend of yours, I think, at National Art School. What was that experience like? Does that make a difference in your career?

Guy Warren 02:14

Well, I’ve just had this email from the people who are organizing the 100th anniversary for the Archibald and they asked exactly the same question. And look, I have to be honest, it didn’t mean a damn thing. Nowadays, I think for some reason, I think Ed Capon, when he was director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, was very good at drumming up publicity. And somehow during his tenure, he made the Archibald into something which was immensely exciting, so that people from the far distant suburbs of Sydney, felt they had to come into the Art Gallery to see the show. I think in the early days, I found when I won it, it didn’t make the slightest bit of difference. I don’t think anybody even noticed that I had – friends did of course, obviously, and other artists did but no it didn’t mean a damn thing – and the money was a lot less in those days than it is now – it was a hell of a lot less.

Maria Stoljar 03:23

That’s right. That’s right. It sort of doubled at some point, I think

Guy Warren 03:24

It was 10,000 when I won it and it’s 100,000 now

Maria Stoljar 03:25

That’s right. And they didn’t have a huge media pack there on the day of the announcement?

Guy Warren 03:28

There was a reasonable media pack, but nothing like it is now.

Maria Stoljar 03:31

Yeah. No, it does. Yeah, that’s interesting, isn’t it? How the prestige of the Archibald has changed over the years. Interesting.

Guy Warren 03:40

Look I’m happy to have won it – it all helped at the time.

Maria Stoljar 03:45

I interviewed Davida Allen and William Robinson together in conversation in Brisbane just before COVID struck. Although they’re friends, Bill is also somewhat of a mentor to Davida. They’re both Archibald winners, and in fact, Bill has won it twice. Here is Davida talking about her 1986 winning portrait of her father-in-law, Dr John Shera.

Davida Allen 04:07

I didn’t paint that picture for the Archibald, interestingly, I painted it from a pure emotion. My father-in-law did the most extraordinary thing. He was a very private man. And he’d always put a shirt on if someone outside the family came to visit. And this one particular day, I visited him, and he was in his garden watering celtis trees, which was like a canopy of privacy around his house in Ipswich. And he didn’t put his shirt on and that piece of life was the blade that went into my artist’s brain – that I have to paint that. But then as I did it, though, I wanted the heightened exercise which is frightening to me personally, I find it really scary when you put the discipline onto yourself that it has to look like that person. It won’t look like that person if you don’t totally know that person. So anyone who knew John, it’s the mouth I got right. It is a John mouth. Anyone who knew that doctor in Ipswich knew it was him because of the mouth. So you don’t have to be totally – the eye, the ear, the nose, the mouth, the physique. You only have to get one or two things right anatomically if you know your subject enough, the instinctive emotion.

Maria Stoljar 05:52

That’s very interesting. William Robinson won the Archibald twice in 1987 and 1995, both times with self-portraits.

William Robinson 06:01

The Archibald is a particularly strange thing, because it’s given a lot of importance. And I thought that there was only one way to go about it when I entered it with me and a cow in the first place showed that – it was to sort of be a bit sort of obscure, and difficult, and rather, not stupid, but – send it up in in a way that not everybody realized that it was being sent up. And so, you know, I used to sort of enter again when I thought I had another way to provoke.

Maria Stoljar 06:52

Would you always inject humour in a self-portrait?

William Robinson 06:56

Well, I think I would, even if I was doing it today. I’m not a person who would paint my life as a series of disasters which I must remember and show with every line in a picture. I’ve had disasters in my life, but they’re not things that I share with other people. I think the last thing that you should ever lose is a sense of humour – about yourself mainly – particularly if you can do it about yourself as an artist because the art business is terribly, terribly serious. It’s still about importance.

Maria Stoljar 07:40

My first ever podcast guest was Francis Giacco, who won the prize in 1994 with a portrait of cellist John Reichard. Can we talk about the day that you won? So what happened on that day? How did you find out?

Francis Giacco 07:56

Well, they told me – I think they rang me up a few days before – it’s announced on a Friday lunchtime. I think they rang me the Tuesday before just to tell me that I’d been chosen. They didn’t say anything about winning. And it was funny because a friend of mine, Peter Griffin, bet me $100 that I would win – which I had to pay him – that’s just a little side story. But it was funny because I was teaching at Ashtons on Friday. And I got a call on Friday morning to see if I was coming to the Art Gallery. I thought ‘This is really weird’. I said, ‘Yeah, I’m coming’. And I went with a group of students. I took about 20 students in – I sneaked them in – I said they were all in my painting. And one of my students knew Edmund Capon, and she said, ‘Capon wanted to know who you were’. And I said ‘that’s weird’. And it was a big crowd of people and the judge, I’ve forgotten his name, it was Hirschon, he was about to announce the winner and I just looked over there and I saw Edmund Capon and his assistant, Claire Martin, and they were looking at me. I thought, oh God, what’s going on here?

Maria Stoljar 09:08

Gee, that must have been a surreal feeling.

Francis Giacco 09:10

It was weird. It was weird. But it’s interesting how you can pick that up out of a crowd. And like you’re there, you know, what are you gonna do – run away?

Maria Stoljar 09:17

You can try

Francis Giacco 09:18

And then suddenly when I was announced, I just remember the students all screaming, because then you’re thrust in front of the camera for the next three, four hours. You’re just asked the same questions

Maria Stoljar 09:27

So you weren’t prepared? You weren’t prepared for that?

Francis Giacco 09:28

I had no idea

Maria Stoljar 09:30

So what was that feeling like – what was that feeling like to have all that attention?

Francis Giacco 09:34

Look, it’s exhilarating, it’s exhilarating and frightening. I had severe pains after a couple of hours. I remember someone gave me some sort of medication. Because I think the nerves in your stomach just become really umm – suddenly you’ve got thousands of cameras on you clicking and clicking, and they’re asking question after question, you know, and, but then – the follow through, there was a lot of criticism. And I had a response to that which was good. They don’t really give that much media response to Archibalds these days except when there’s controversy

Maria Stoljar 10:09

What was the main criticism?

Francis Giacco 10:11

Well, not technically a portrait. I mean, this is you know, this is a competition where Bananas in Pajamas can get chosen as being a portrait, you could do an abstract and call it a portrait but because, you know, I had five portraits in one. I met all the trustees except for Tim Storrier and they all told me that it was a unanimous decision – straightaway they thought, they thought it was a fantastic painting – that’s what they told me and that there was no other, there was no runner up. Bill Leak had a portrait of Malcolm Turnbull so I tried to get Paul Delprat to tell Bill Leak to be nice to me. I was terrified. But we had a forum at the Intercontinental and I was up on the stage with Bill Leak and Malouf, Anne Thomson, Edmund Capon, asking questions. One of the criticisms was that I said, ‘Look, I feel a bit like Rembrandt when he painted ‘The Nightwatch’ because Rembrandt was criticized for not giving everyone equal prominence in his portrait, ‘The Nightwatch’. And then in this book on the Archibald, ‘Let’s Face It’, it said I compared myself to Rembrandt.

Maria Stoljar 10:27

Oh for goodness’ sake

Francis Giacco 11:19

That’s how they take these things, quotes that you say and distort them

Maria Stoljar 11:23

It is, it is one of the problems

Francis Giacco 11:25

I did get a lot of support. John Olsen was a support. Even Edmund Capon was being very supportive.

Maria Stoljar 11:32

And I’m sure most people who would have seen it in real life would have –

Francis Giacco 11:36

Oh the crowds were huge. I remember going I couldn’t see the painting, the crowds were just

Maria Stoljar 11:40

Yeah it’s a great painting. There’s no doubt about it. So I presume after that you were you weren’t an unknown anymore, that’s for sure.

Francis Giacco 11:49

No, then galleries were ringing me up and asked me for shows. Suddenly, you know, nobody wanted to show me and suddenly… Winning the Archibald gives you a boost. You know, I always say it’s like, it’s like being good looking or having lots of money or something, it gives you that push, you know, it’ll take you a certain distance. It’s not going to last forever.

Maria Stoljar 12:07

Wendy Sharpe won the Archibald prize in 1996 with her self-portrait as Diana of Erskineville.

Wendy Sharpe 12:14

It’s a tongue in cheek kind of painting. It’s me sitting in a studio surrounded by paints and all sorts of painting detritus from a studio. So when you asked me about, say, seeing old painting, say in the Louvre, for example, that one painting absolutely relates to those paintings. It relates to Reynolds and Gainsborough and all of those 18 century paintings of the Duke of somebody or other or his wife, and all these attributes that tell you how great he is – like he’s often standing there in fancy robes with a globe to show he’s traveled, or something or other to show how rich he is or something to show he’s gone on the Grand Tour. There’s all those things. It’s relating to one of those. So it’s absolutely relating to that – that’s what I was thinking of. But I’m surrounded by a load of sort of things – of broken crap around in the studio. But I’m also dressed as Diana, who is the goddess of the hunt, Roman version of Artemis, Greek one, so she’s the goddess of the hunt. She always has a little moon on her head, which is what I have in the painting – I’ve got a little moon. And I’ve also got plastic bows and arrows which is all that- and I’ve also got a bit of a leopard skin printy thing, which is what she had too – because she’s a huntress – so it’s this thing about having to be tough and strong and being a fierce warrior kind of thing but being a painter so it’s a bit of a joke. But the other part of the joke if you like, or a bit of a joke, is Erskineville which doesn’t really work now because Erskineville where I’ve lived for years, forever almost, was in those days a really rundown working class suburb, very cheap houses, that was funny – would have made you laugh at the time that there could be any goddess coming from Erskineville because it was the last place – whereas now it’s so gentrified and so posh that it sounds like that this is a goddess in some really, really upmarket inner city groovy suburb

Maria Stoljar 14:13

(haha) So the joke doesn’t work anymore

Wendy Sharpe

(haha) That’s right – it just means that she’s an inner city wanker. Really, it’s a different type of thing.

Maria Stoljar

Right. And was part of the idea also that it’s a woman in the art world?

Wendy Sharpe 14:25

Yes. Yeah. It’s all of those things.

Maria Stoljar 14:28

Did you find that was something that you felt back then? Or now?

Wendy Sharpe 14:33

Yes, it’s still there. It’s still there. I mean, you know, even to be sometimes presented even now, as a ‘woman artist’, you know, you don’t call them ‘men artists’, call them ‘men artists’ ‘he’s a man artist’. So, you know, it’s just so easy to find out ‘Is this sexist? Is this racist? Is this wrong?’ Just reverse it. Oh, yes, it is!

Maria Stoljar 15:01

Lewis Miller won the prize in 1998 with his portrait of artist Alan Mitelman. I’ve actually spoken to a few of my previous guests who were Archibald winners. Luckily enough I’ve interviewed a few Archibald winners and it seems to be a pretty intense experience.

Lewis Miller 15:17

Yes, yes.

Maria Stoljar 15:18

What’s your memory of it?

Lewis Miller 15:19

Well, it was very intense for me the day before the announcement, because I’d gone up by myself on the train to Sydney. And I hadn’t seen my picture framed – it had gone from the framers. And they had this lunch, the day before the announcement – they still do that – with the guides, they ask questions about why you painted so and so, who you are, if this is your first time, and then during the lunch, you’re allowed to go down while they were hanging the Archibald. The last year when I went, it was already hung and the lunch was actually in the gallery, but that was new. But when I went down, and I saw my painting, I thought, ‘Oh shit, I think I’m gonna win. Oh, no’ I really had this strong, strong feeling because it looked really big for a start. It looked sort of quite captivating or something. But I thought, ‘Oh, no, don’t think that, don’t think that’.

Maria Stoljar 16:17

Why don’t think it because you don’t want to get your hopes up?

Lewis Miller 16:19

Because I knew they hadn’t judged it yet. So I kept on talking to that little voice in my head saying, ‘Don’t be silly. Don’t be ridiculous’. But I couldn’t – the other voice was saying, ‘Yeah, you’re gonna win.

Maria Stoljar 16:33

So was it the next day after you had seen it that it was announced?

Lewis Miller 16:38

Yeah I was staying at a friend’s place in Paddington, and it was quite hot. And I was wearing shorts and a T shirt. And thongs, I think. So I got the taxi, I don’t know why I got a taxi, but I got a taxi to Ray Hughes gallery in Surry Hills. And I walked in and Leah Haynes, who was Ray’s assistant said, ‘Oh you can’t go to the press launch like that with shorts on’ and I said ‘Oh but I’ve just got a taxi all the way from Paddington’. It was $7 or something. She said ‘Look, just go back and iron your shirt and come back, and then we’ll go off to the thing together’. So I thought ‘Why’d she say that? Why’d she say that?’ So I went back, ironed my shirt, put on my jeans and I walked in and Ray said ‘You won’ and I said, ‘Oh, I’ve gotta ring my Mum. Is it alright if I ring my Mum?’, ‘Yeah ring your Mum’ So I rang up and dad answered. I said, ‘I won dad’ and he said, ‘I’ll get your mother’. Which is very sweet. And mum said, ‘Are you sure darling? Are you sure?’ and I said, ‘Yes, Mum. This time, I’m sure’ because there was a time when there was a rumour and I hadn’t won. So she really wanted to know. I said ‘No Mum I really have won this time, they rang up Ray’ and I said ‘and I spoke to Alan, and he’s on the way now to Sydney, so they must have called him as well’

Maria Stoljar 17:59

So why did you think of ringing your Mum as the first person?

Lewis Miller 18:02

It was me Mum! Yeah, I just – because I know how interested and keen she was on it. You see my father had entered the Archibald in 1967, which is 50 years ago, and my brother and I had to get out of our bedroom so that Dad could have a studio to do this painting, to do this portrait. And he got in, but he never entered it again. But that was the seed that was planted in my head 50 years ago, from when we had to get out of our room. And I remembered that and so I must have been there. But I’m surprised that I didn’t enter earlier. Why I wasn’t entering when I was in my early 20s

Maria Stoljar 18:43

Yeah

Lewis Miller 18:44

I think in a way it was seen to be a Sydney exhibition, was seen to be a little bit exclusive and I didn’t realize that you should just have a go.

Maria Stoljar 18:55

In 1999, Euan Macleod won with his self-portrait ‘Head like a hole’. What was that experience like?

Euan Macleod 19:04

Yeah it’s a pretty weird experience. And yeah, look, the painting again came up, in that I was doing a painting. It wasn’t actually done for the Archibald. I was just doing this painting and then I kind of thought ‘Actually that would be quite good for the Archibald’ and I thought that it might have a chance of getting hung because it was a bit wacky. I had entered the Archibald, I think twice before but not sort of seriously. And this one I just thought ‘oh, look, you know, it’s a bit of a throwaway, you know, put it in, you never know someone might think it’s funny enough to hang’ and that year they were looking for a painting. That’s what they were looking for. I found out later. One of the trustees was saying ‘We want to give it to a painting, not a portrait’, just trying to push the parameters of what the Archibald prize was. So they were kind of looking and, you know, the difference – a portrait can be a good painting and a good painting can be a portrait and all that but sometimes there is a difference, I can understand what they were saying. And just luckily, mine fulfilled the brief.

Maria Stoljar 19:51

Were you surprised it won?

Euan Macleod 20:25

Oh I was really surprised. I was absolutely shocked that it won. I kind of thought I didn’t push any of the buttons for winning. I mean, I hadn’t been in it before. Watters Gallery generally hate prizes and certainly don’t pander to that kind of thing like some galleries do. I guess I had a lot of misguided ideas of how it worked and I actually was wrong. I think sometimes the trustees just kind of judge something they like, and you know, they’ll just say ‘No I don’t care if that one should win it, this one’s gonna win it’ and a lot of people are critical of that, a lot of people say they wouldn’t know a good painting if they fell over it, there’s a lot of harsh criticism of it. But look, the whole system kind of works and I’ve got to say for it that they are their own people There’s nothing like a competition that’s not really a competition, where it’s rigged, where it’s basically you know who the judge is going to pick, the judge is chosen because the judge likes that work, and that’s, you know, so it’s a sort of competition, but it’s not really a competition. So the Archibald I think, has qualities that I admire but because of its status and because of the fact that the public feel they have a part in it all, and are asked to have a part in it, it becomes very hard for the artist because there’s a lot of criticism of the winner, terrible criticism, and it’s pretty harsh and it’s pretty personal and it’s pretty nasty. And, you know, quite vicious and I don’t like having people saying nasty things about my work at the best of time. But this was sort of on national TV and I’ve kind of realized that everybody comes in for that to a certain extent. Some people get less of it and some people get more of it.

Maria Stoljar 22:40

Well some people think the more controversial it is the better

Euan Macleod 22:43

And there is an encouragement to make it controversial because they know that gets publicity

Maria Stoljar 22:54

So you found it a very uncomfortable experience

Euan Macleod 22:57

I did I did and I’ve got two photos – one of me after I won the prize where I’m sort of looking totally shocked and one the year when the next person won it and I’m just looking like a weight’s been lifted off my shoulders. But, you know, the Archibald prize – the benefit of it is that it involves the public and whatever can involve the public is so fantastic.

Maria Stoljar 23:25

Nicholas Harding won the prize in 2001 with a portrait of actor John Bell. I just want to talk firstly, because I have interviewed a few Archibald winners and it’s interesting because they’re all varied reactions to that experience and not all positive, actually. So I was just wondering what your experience was?

Nicholas Harding 23:49

Well of course, to win that prize is incredibly exciting and a marvellous thing, I mean it’s terrific. So it’s mostly, of itself, it’s a wonderful thing. I suppose if you’re going to find a downside is the way it messes your head a bit because all of a sudden for five minutes everyone wants to know what you’re doing and what you think. Not necessarily about anything that you necessarily thought about. Journalists ringing you up for your opinion on any kind of matter of the day that –

Maria Stoljar 24:30

Oh not necessarily painting?

Nicholas Harding 24:32

No no and all of a sudden apparently you’re qualified to make remarks about something you hadn’t really paid that much attention to. Sometimes it is something you’ve paid attention to, but not always.

Maria Stoljar 24:46

Yeah, well, you’re sort of a celebrity in a way.

Nicholas Harding 24:48

Yeah you are, I guess you are. It’s a small pool in that regard in terms of celebrity. You’re not a football star and you don’t play cricket for the country and you’re not a soapie star or in the movies or anything, but it is a celebrity of a kind.

Maria Stoljar 25:10

Were you expecting to win?

Nicholas Harding 25:11

No, not really. I mean, people were tipping me, definitely. But that was my eighth time in it and I’d had a couple in the Refuse and it was kind of like ‘Well, really?’ There’s usually something else in the room that gets there.

Maria Stoljar 25:27

And I think it was the second time you painted John Bell.

Nicholas Harding 25:39

It was. I painted him the previous year. And that was to acquaint myself, because I always had in my mind to paint him as King Lear because that was my initial impulse to paint him. But I didn’t know him and I had to paint him. I’d done a few very quick sketches from memory when I got back from watching him as King Lear. We were in the front row, in the middle, so prime seats. And that was the thing, that was the impulse. You know, that was that initial impulse that drives the creation of a work.

Maria Stoljar 26:09

Well, I hear that he saw the sketch and he actually contacted you

Nicholas Harding 26:13

Oh that was a different sketch.

Maria Stoljar 26:14

Oh, is it a different sketch?

Nicholas Harding 26:15

Yeah. And that was some years before, so we had seen him in Coriolanus at the Seymour Centre which I think was directed by Steve Berkoff. I could be wrong on that. But I did a just an ink and paper drawing of him and one of their donors, sponsors supporters bought it and donated it to Bell Shakespeare. And then John, who we actually met at morning tea at our mutual friend Rex Irwin’s some time beforehand, and, you know, we’d liked each other’s company and it was the beginning of a good friendship. But we hadn’t seen each other for ages. But he sent me a nice postcard and said, if you ever want to have me sit for the Archibald just let me know. So when I saw him in King Lear, a little bit later, I got in touch with him, and he’s a very busy man, certainly back then he was very, very busy, so the only sitting initially to do a drawing was at lunchtime when he was rehearsing ‘Dance of Death’, a Strindberg play, down at the Wharf. And I’d arrived early, so I parked outside and was reading the paper waiting for the allotted time and then I noticed he came out to walk his dog and he was still obviously still in that Strindberg – he was still the Colonel – he was in that liminal space of not quite himself and not quite the character. But he had this look on his face, it was very intense and would help inform my portrait of King Lear later on. Anyway, he took the dog for a walk. And then we did the drawing.

Maria Stoljar 28:03

Del Kathryn Barton was my other guest who won the prize twice, in 2008, with a self-portrait with her children, and in 2013, with a portrait of Hugo Weaving.

Del Kathryn Barton 28:16

The most, and I’m sure a lot of the artists you’ve talked to that have had the crazy Archibald experience would say the same, the most fascinating, in some ways problematic, but wonderful thing about the Archibald is the audiences that it reaches. The week that I won the Archibald with the self-portrait with my children I also had my first solo show in Melbourne open. So that was, again, just a real blessing too because it just meant that thousands more people saw that show that they wouldn’t ordinarily. And because portraiture, I’m very passionate about portraiture, but it is essentially an adjunct to my figurative practice. So not necessarily that representative of my core, figurative practice. It does mean a lot to me. And actually the same week, it was a big week, I had a painting on the cover of what was Art in Australia then. So, which again, was a very different kind of painting to the painting that was in the Archibald. You know, it was a beast woman with her boobs out. So I sort of feel like all of that coming together was a pretty extraordinary moment for me. Yeah.

Maria Stoljar 29:47

Well, do you find that with the portraiture in the Archibald, the requirement to get a likeness or the desire to get a likeness is what is setting it apart from your other work? Is that the main difference do you think?

Del Kathryn Barton 30:01

I see that as being only one aspect. Because I find – and certainly making a self portrait eliminates the stresses of what I’m just about to describe – but certainly working, like painting someone – and in the context of the Archibald, it’s going to be someone you admire enormously – is just a huge, committed experience to step into with just layers and layers of …

Maria Stoljar 30:36

pressure?

Del Kathryn Barton 30:37

Yeah. searching around for some euphemisms, because it’s very, it’s a

Maria Stoljar 30:44

Well people like Cate Blanchett and Hugo Weaving…

Del Kathryn Barton 30:47

Absolutely! The first time I met Cate, I was really – she’s always been one of my heroes and I found that incredibly special and we’ve worked together in other capacities since. She’s so down to earth, but it was a very, very overwhelming experience. And I’m a real pleaser, too, although I can be, yeah, as I said before, I have a lot of fortitude now and single-mindedness, but if I’m going to work with someone and to give something to someone, or to represent someone, I want them to be happy, like, so all of that. And then the fear of not being a finalist, and yeah, it’s a lot.

Maria Stoljar 31:32

Would you still feel that now?

Del Kathryn Barton 31:34

Definitely.

Maria Stoljar 31:38

Do you feel it for your sitter?

Del Kathryn Barton 31:42

Absolutely! Yeah, I think being a bit older and tougher now, I think there’s a lot of camaraderie that goes into also potentially not being hung.

Maria Stoljar 32:00

Yeah, so you’d share your commiserations with friends or whatever, who didn’t get in?

Del Kathryn Barton 32:04

Totally. Or if, say, I sat for a portrait, and then that wasn’t hung that there would be a special bonding that would come out of that with a painter – I mean it would be more fun for us to be hung but, you know, (laughs)

Maria Stoljar 32:17

At the lunch? I must say that, as you know, I interviewed Marc Etherington who painted you for the Archibald and he was a finalist and I love that painting.

Del Kathryn Barton 32:26

I loved it too.

Maria Stoljar 32:27

That must have been a fun experience. It was so funny when he was telling me that he had never sketched a person from life before. He had to go out and buy a sketchbook.

Del Kathryn Barton 32:40

I just love that man so much. He’s a special, special human.

Maria Stoljar 32:46

In 2009, Guido Maestri won the prize with his painting of Dr. Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu Was that the first time you’d been a finalist? And you won it?

Guido Maestri 32:58

Yeah

Maria Stoljar 32:58

How was it? What was it like?

Guido Maestri 33:00

Oh, well, I enter prizes with no, you know, thoughts about anything. I just always enjoyed entering it. I was entering it from the second year at art school, because I just wanted to. I knew I’d never get in, but I just liked that I had to make a painting and finish one and you get to go down there

Maria Stoljar 33:27

To the loading dock?

Guido Maestri 33:28

Yeah the loading dock. It was cool, it was like ‘behind the scenes’. So I loved doing it and I never thought anything would happen anyway.

Maria Stoljar 33:42

What sort of people would you be painting? Were they sort of –

Guido Maestri 33:45

Well I think a lot of the reason that that one got in was because it was just such an extraordinary subject.

Maria Stoljar 33:54

I should mention just for the listener that Gurrumul, he has since died, but he was a famous Indigenous singer.

Guido Maestri 34:02

Yeah, absolutely, utterly extraordinary. I saw him and just, that was it. I never felt more compelled to paint someone, just, you know, the idea that okay, if this gets hung, then people will see this, and they’ll talk about the subject, they’ll talk about him. And for me, that was the most successful thing about it. I remember going there on the night and they were playing Gurrumul’s music through the whole Art Gallery. And I just thought that was the best thing that has ever happened to me from a painting.

Maria Stoljar 34:44

Ben Quilty won the prize in 2011 with his portrait of artist Margaret Olley.

Ben Quilty 34:51

The painting of Margaret was a homage to a friend, really, a friend and a mentor although I don’t like the term mentor. She was a friend. She was a good friend who stood up for me, who taught me how to stand up for myself. And yes, possibly that’s mentorship

Maria Stoljar 35:07

In what way did she teach you to stand up for yourself?

Ben Quilty 35:09

I watched her do it. She’d belittle politicians in front of me, which was awkward. I was a very young man and she’d put them in their place. She stood up for herself. And she was a very, very shy young woman who became probably still a very shy human, but she knew what she believed in and she wasn’t scared of anyone. She held artists in the highest regard. Artists were the people who should be ruling the earth through Margaret’s eyes. And I thought, What am I worrying about? Why am I playing this second role to people I feel in a societal hierarchy that I’m lower than them. When you sit with Margaret Olley, no one, except the artists, were below her admonishment.

Maria Stoljar 35:59

Oh, right. So the artists she held in the highest esteem

Ben Quilty 36:01

Yeah I was at a lunch with Margaret at her home. And there was the premier of NSW was there, Edmund Capon was there and Nick Mitzevich, who’s now become the director of the National Gallery was there, and Nick and I were friends back then and he was the director of Newcastle Regional Gallery and I said ‘Margaret’, I stood up to start clearing the table. And she said ‘Ben, sit down! Edmund, clear the table’. And I was appalled. It’s like – Edmund glanced at me as I sat down – I was not going to disobey Margaret. But everyone was below her artists.

Maria Stoljar 36:40

Right. I think she sort of took a lot of people under her wing from what I’ve heard.

Ben Quilty 36:44

Yeah, she just stood up for artists – when you look back at – and musicians, I mean, there are classical musician that she kept like that, and artists. I mean, there were lots of them; Nicholas Harding, Cressida Campbell, there was a group of us and that group was growing and growing and the longer she lived, the bigger that group became, and they were people she fought for. And really, she wasn’t fighting individually for us. She was fighting for acknowledgement of visual language of the arts.

Maria Stoljar 37:14

Tim Storrier won with a self-portrait in 2012. He was also on the board of trustees of the gallery in the 90s. And it’s the trustees who decide who wins the prize. In this clip, he gives some insights into that process. You were a trustee of the Art Gallery of NSW so you would have been involved in selecting the Archibald prize in the 90s. How was that experience for you when you actually won it?

Tim Storrier 37:43

Well, I wasn’t expecting to. Although having said that, you don’t enter it unless you want to win it. But it’s a chook raffle

Maria Stoljar 37:53

Yes I was going to ask you about that.

Tim Storrier 37:56

I know the decision making process very well. And it’s as good as you’ll get but it’s a committee decision. And if there’s no agreement, it can go wild, you see. So you don’t really know. And it depends on the number of people on the board, like, Who are they? What’s their experience? The personalities play a big part in it. So you don’t really know.

Maria Stoljar 38:17

So, just for people who don’t know, maybe overseas listeners, the Archibald Prize is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and a group of people who are on the Board of Trustees, they’re the ones who decide who wins the prize, and they’re not just artists, and in fact –

Tim Storrier 38:33

No there’s only two artists on the board. The rest of them are business people.

Maria Stoljar 38:36

Yeah so it’s a really interesting prize. Did you generally feel as though the right one was chosen each year when you were a trustee?

Tim Storrier 38:46

Well, I mean, one always has a view on that. And as a rule, force of argument could come into it. Numbers come into it. It is a committee so you’re not always completely happy. And sometimes you’re very unhappy. But as a rule, yes, I think they made the right decisions, mostly mostly.

Maria Stoljar 39:07

Did people often look to you for your opinion because you’re an artist? Yes. And also I suppose you could have sort of analyzed it from that perspective?

Tim Storrier 39:20

Well yes but force of argument comes into that but you may or may not win. It’s a very tricky thing because, as you will know, when you’re dealing with aesthetics, everybody’s got an opinion. A lot of the opinions that are put forward aren’t particularly advised so force of argument really is very important if the decision is split.

Maria Stoljar 39:50

Yeah, and I suppose that argument has to be backed up with reasons.

Tim Storrier 39:55

Yes, of course and it can be with a trained person. And by the way, it’s quite interesting. You find quite often that a businessman or woman, and most of these people are pretty highly intelligent because of their career successes or getting to these places, you find that quite often, they can form a very good argument in support of what they believe about aesthetic matters. Look, what you’re going to get me to say, which I don’t particularly want to say, is that it’s imperfect.

Maria Stoljar 40:30

Well, I suppose judging any art prize is going to be an imperfect exercise

Tim Storrier 40:34

Well, it’s idiosyncratic. There’s no doubt about that.

Maria Stoljar 40:38

And also, I’ve heard people say that they won’t enter a particular art prize, because the judge is not going to like their particular style of work

Tim Storrier 40:47

Exactly, they’re smart.

Maria Stoljar 40:50

But don’t you feel that you’re going to be attracted to a painting that is more in line with your aesthetic preferences, you know? Maybe not your style of painting, but –

Tim Storrier 41:05

No, I would say that’s absolutely not the case in my position I mean, when you take on a role like that, you’re almost duty bound to put in the back pocket what you might think, but it could also be prejudicial. So you have to take what used to be called a Catholic view, which is a broad view. And you have to maintain that. Otherwise you’re being unfair and prejudicial to a certain type of work.

Maria Stoljar 41:38

So what would you have been looking for when you were looking at paintings?

Tim Storrier 41:42

That’s very difficult. Well, paintings of high quality essentially. And a very humanistic and interesting interpretation of the human face and figure, I would say. See, it’s already morphed away from what it was. It was a portrait prize for portraits of people who are highly respected in the arts, science, politics and letters, basically, you know. Well that changed

Maria Stoljar 42:20

Yeah there’s a lot of self-portraits and a lot of portraits of artists now,

Tim Storrier 42:26

Not to say that they can’t be very good.

Maria Stoljar 42:28

No, but also I think it’s just easier. And also, I mean, once you start painting a politician I mean, I don’t think anyone wants to paint a politician anymore

Tim Storrier 42:38

No, I think that’s true, but there’s going to be reaction against the number of self portraits

Maria Stoljar 42:44

Yeah, I do agree with that. I think last year was there was a record number but I’m looking forward to the 100 years actually, which is in two years’ time. So that’ll be fun.

Tim Storrier 42:59

Maybe

Maria Stoljar 43:00

and also the public loves it. You know, everybody loves going and

Tim Storrier 43:06

The quality’s dropped dramatically. I believe that this last year it was a fantastic opportunity for the trustees not to award it. To sharpen it up. They’ve done that before

Maria Stoljar 43:16

Yeah, that was done once before wasn’t it? That’s a bit harsh.

Tim Storrier 43:21

Why?

Maria Stoljar 43:22

Because I think the calibre is pretty good. I think the quality is pretty good. Look, you’re always going to get some that aren’t, you know, that you sort of think ‘how did that one get in?’ Although sometimes you go to the Salon des Refuses and you think ‘wow, that one didn’t get in and you know, it should have’

Tim Storrier 43:40

Well you know my position. I did a painting of McLean Edwards, they didn’t even hang it and yet it won the –

Maria Stoljar 43:46

– yeah, the Doug Moran.

Tim Storrier 43:48

Yeah

Maria Stoljar 43:51

Louise Hearman won the prize in 2016, with her portrait of entertainer, Barry Humphries. Was he keen to have his portrait painted, was it your idea?

Louise Hearman 44:01

It was my idea. I just got to know him. And I had this idea and I had sort of, after I’d seen his final performance, he was standing in front of the curtains as Barry in Melbourne, his hometown, I felt this real sense of kind of sadness, because it’s the end of an era that he’d finished. That’s his last performance, but apparently he’s done a whole lot of, you know, ‘after the… after the… after the…’, He’s never going to stop. But I thought ‘I must paint Barry for the Archibald because I’d never thought of the Archibald before because I’d never thought – I’d seen people that are definitely worthy subjects, but I hadn’t worked out a way I could paint their head. For example, Richard Tognetti, Richard and his wife, wife? girlfriend? Satu – they introduced Bill and I to Barry so they’re both worthy subjects. But I couldn’t get my head around Richard and I’d been thinking about Satu but I might get back to Satu one day

Maria Stoljar 45:12

Was the white jacket in the painting something you requested?

Louise Hearman 45:15

No. And it’s so brilliant because I kept on asking Barry to come back because – and he’s so beautifully dressed. He’s like a lyrebird isn’t he? and I feel like Madge always next to – I don’t care, I couldn’t be bothered dressing. And he hates black, ‘oh black, black – so boring’, but I’m always wearing black. But the day he turned up with that jacket, that outfit on, I just went ‘This is perfect’, because it’s not throwing any colours, particular colours up onto his face, I just love it, it’s neutral. And it was just perfect.

Maria Stoljar 45:52

Having that dark background with his face emerging in the light, what influences you to create that sort of effect?

Louise Hearman 46:01

Well, my original idea was much more complex. So it was a vision I had and it would have been quite a busy background. But as I went along, I went ‘no I don’t need that. I want to focus on Barry. I don’t want to focus on the storytelling the hieroglyphics of ‘oh this is Barry, he’s this, he’s that, he’s whatever’. And also the way I think is singular focus, although people say I’m all over the shop, which I am – I chop and change – they can’t follow what I’m talking about. And then I lose track of what I’m talking about. But in painting, making images, I tend to have a singular focus in a picture. Otherwise I don’t know what I’m doing. So, for example, when I was painting the MCG crowds for the Basil Sellers Prize, which I didn’t win, I could only paint the crowd if it wasn’t individual objects. I could paint it if they became a mass of one thing, I just can’t do more than one thing.

Maria Stoljar 47:10

In 2019, Tony Costa won the prize with his portrait of artist Lindy Lee.

Tony Costa 47:17

Only three people saw the painting before it went to the Archibald, and all three people said, ‘Wow, that’s Lindy’, and I was thrilled because none of them knew that I had painted Lindy and so I knew it was genuine. So that’s always a lovely surprise.

Maria Stoljar 47:34

Is it important to you to keep it really under wraps?

Tony Costa 47:38

I think so, it dilutes the tension between myself and the sitter. And you know, you don’t want to be talking about something you haven’t even created yet. Because the big question is who you are painting next year, and I honestly don’t have anyone for next year. But even if I did, I think I owe it to the sitter to keep that quiet.

Maria Stoljar 47:56

Now the other thing that you told me, which I am astonished by is that with Lindy’s portrait, you worked for 16 hours with a 10 minute break for lunch.

Tony Costa 48:09

That’s right, I’m on a roll

Maria Stoljar 48:10

What was that about?

Tony Costa 48:12

Well, it’s about being in that zone. You can’t possibly leave the painting. I think I don’t want to leave the painting. And if I’ve got the energy to keep going, well, then I do keep going. And that’s usually the tendency that if I start a painting, I’ll start particularly early. So normally I start at seven o’clock in the morning, knowing that by seven o’clock at night, that’s already a 12 hour shift. And that I’ve got the latitude to go another four till about 11 o’clock at night. And by that stage, I’m pretty wrecked, I’m ready to die.

Maria Stoljar 48:45

That is not a usual situation I presume.

Tony Costa 48:49

It only happens when I’m painting very large pictures. And I want the one skin and I want the one mark and the one energy to go through the entire picture. If I was to go back to the painting the day after and the day after that, not only would I begin to tear the surface which then starts to dry, I would run the risk of contaminating and making the painting look tired.

Maria Stoljar 49:11

In 2020 Vincent Namatjira was the first Indigenous Australian to win the prize with his self portrait with Adam Goodes. You’ve done a portrait of Adam Goodes and you’re in it as well. How did that feel to win?

Vincent Namatjira 49:28

To me, like, it was ‘I’m not going to win, I’m not going to win’ – it was that kind of feeling at first because I’d entered already four years. And I’d been shortlisted, shortlisted, shortlisted and shortlisted. But on the fifth year, it finally comes around the announcement. One day I was sitting at home and my manager from the Art Centre and his partner and child came knocking on the door early in the morning, got me out of bed. They didn’t say anything. They just said ‘Morning’ and just handed me the mobile phone. And there was a fellow on the other side. He was one of the judges from that Archibald prize. And ‘Vincent? Am I speaking to Vincent? Hello, Vincent. I’d just like to tell you, you are the first Indigenous to win the Archibald prize. Congratulations.’ Yeah, I looked and said, ‘I’ve win’, I said to my manager, and his partner and colleague and they just – Yeah, yeah. Paralyzed in the face.

Maria Stoljar 50:39

Oh, yeah. Well, I could imagine that Iwantja Arts must have been like going crazy. And the whole Indulkana community must have been so excited

Vincent Namatjira 50:49

Yeah we’re really supportive. And we always work together in the Art Centre. We don’t like trouble in the Art Centre whatsoever and maybe a little bit of humbug and noise we like to keep it. There’s normally a full house, we have 30 artists in the Art Centre at Iwantja.

Maria Stoljar 51:09

Now, also, I want to just quickly talk about the Archibald painting itself, because I love that painting. And I noticed when I was looking at it, that not only does it have sort of a narrative to it with Adam in the background, but also, the colour palette you used is basically red, yellow, and black which are the colours of the Aboriginal flag. Is that a deliberate thing? Or is that just something coincidental?

Vincent Namatjira 51:33

Coincidental

Maria Stoljar 51:34

Oh, was it?

Vincent Namatjira 51:35

Yes, the main thing that I was working on that canvas was the footprints, which was on the bottom of it. And that pretty much sums up everything that was on the canvas. ‘Stand strong for who you are’, is the title of that canvas and that footprint on the ground, it was actually my foot, walking over the canvas. So I painted red on my foot on the bottom, and walked on the canvas, which pretty much sums it up all together ‘Stand strong for who you are’

Maria Stoljar 52:07

Peter Wegner won the Archibald this year with his portrait of Guy Warren, who is also a podcast guest and who himself turned 100 this year.

Peter Wegner 52:18

I’d like to really thank Guy Warren for sitting and for his generosity of spirit. And he really, I mean, it’s so much easier if you’ve got a great face. And I think it’s always easier if you have a great model. And I think in the case of Guy I’ve been extremely lucky. I had both. So it’s a big thank you to Guy. But also Guy is probably one of the most remarkable 100 year olds I’ve ever met. Now I say this because I have drawn, painted and sat with over 90 centenarians in a series I’ve been doing for seven years. And this was the reason I approached Guy to sit for me. And it wasn’t actually the idea of the Archibald I had in mind. But as it works out it’s very well timed on both levels. I still think it’s extraordinary, to live on this planet for 100 years and still have a sense of purpose, curiosity. And maybe this is the reason for Guy’s longevity. So Guy Warren I have to thank you very much and I’m hoping you’re there today and that you enjoy this with me.

Maria Stoljar 53:37

William Dobell controversially won the prize in 1943 with his portrait of Joshua Smith. His biographer Scott Bevan talks with me about that time. Let’s just briefly describe the painting for people who maybe can’t get to their screen and bring it up, and might not have ever seen that work before. It was Joshua Smith seated with his elbows resting on the armrests of the chair and his hands crossed in front of him.

Scott Bevan 54:09

Correct. And you would notice those hands, you cannot help but notice those hands. We were talking before about Dobell’s attention to hands. And Joshua Smith’s portrait is certainly an example of that. But it wasn’t the hands that grabbed everyone. It was that face. And people were going, oh my goodness, has he exaggerated this? Has he elongated this? Has he made this guy look this ugly, or is this a representation? And so began the controversy.

Maria Stoljar 54:41

Exactly. And quite elongated arms and neck as well I would say which is quite striking when you first see it. And of course it won.

Scott Bevan 54:51

It did.

Maria Stoljar 54:52

Can you tell me a little bit about what the reaction was, say, the next day and Joshua Smith’s reaction?

Scott Bevan 54:59

Yeah, well there was this culling down of the finalists by the trustees until there were two left, two portraits that the trustees were determining who was going to be the 1943 Archibald Prize winner. There was William Dobell’s portrait with the artists. And there was Joshua Smith’s portrait that he’d done, which was Mary Gilmore.

Maria Stoljar 55:23

Yeah, the writer

Scott Bevan 55:25

and the poet. And the vote was seven to three. And so Dobell won and that was duly reported. And then the next day, on the Saturday from memory, I think it was Maria, the public, the media got to see, could come in and be face to face with the winner and, as it turned out, the future of Australian art, where Australian art was heading. Some would look at it and think, ‘Wow, at last, the shackles of those moribund, conservative portraits that have defined the Archibald to now have finally been cast off’. Others thought they were literally looking at the ugly face of modern art, and thought something wicked and horrible this way comes. Art as we know it is over in Australia if this is going to be the future. And everyone had an opinion, including Joshua Smith, and Joshua Smith’s parents who were there. And the media made a beeline for the parents and said, What do you think? And the parents were apparently influenced by hearing some of the comments that were less than flattering, and they were worried for their boy.

Maria Stoljar 56:37

Yes. And it sounds like that rubbed off onto Joshua Smith himself and he changed his view.

Scott Bevan 56:44

He did. And those who knew both of them said that all the way along, Joshua was happy with what was being produced with the representation. And Joshua became more and more perturbed and disturbed as this became not just the winning portrait, but a point of conversation and contention, that the Archibald prize, more than ever before, was not just opening eyes – and Dobell wanted to open eyes with his art, that’s what he wanted – what it was doing was opening mouths, and everybody, everybody had an opinion. And everyone was saying, ‘Do you reckon that’s a real fair dinkum portrait? Or do you reckon that’s a caricature?’ And so, that very question was leading not just to the court of public opinion, it was leading towards a court of law.

Maria Stoljar 57:42

You can hear what happened next with that court case by going to Episode 96 of the podcast. Or better still, why don’t you buy Scott’s book which is called Bill: The life of William Dobell, an absolutely brilliant read. Also the exhibition, Archie 100, which is an exhibition of significant portraits which have been hung in the Archibald prize, which unfortunately was cut short at the Art Gallery of New South Wales because of COVID, will still be travelling around the country, so it’s worth having a look out for where it’s going on the Art Gallery of New South Wales website. Thanks for listening and hope you can join me for the next episode of Talking with Painters